TAMARA FAITH BERGER'S 'LITTLE CAT'

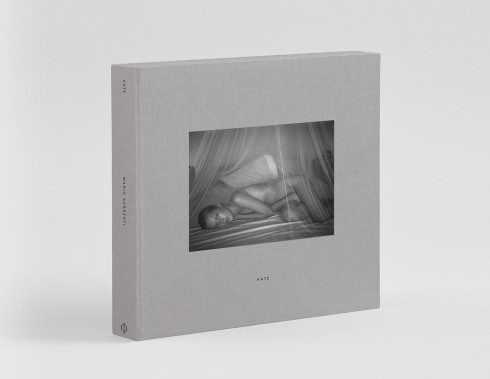

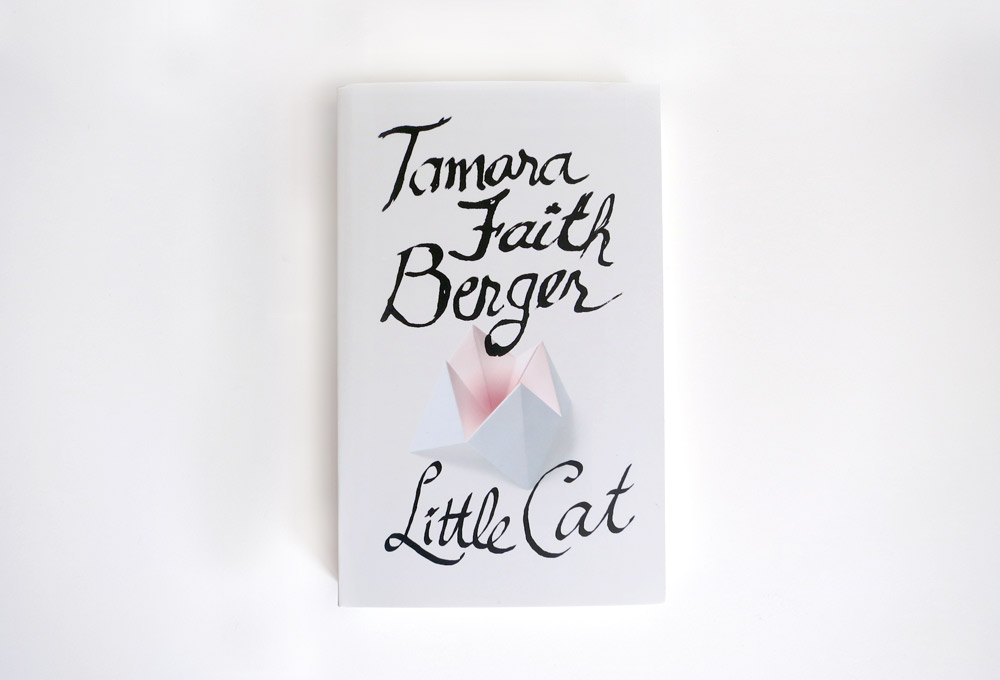

Tamara Faith Berger’s Little Cat, a new collection of the writer’s first two novellas, is presented as a demure, simple tome. The book’s look is minimal and sleek, not overeager; a design house could coolly call its æsthetic a “sophisticated approach.” Its covers are colored a mature matte cream. Their only picture is a geometrical and alluringly vague paper fortune teller. Inside, there are elegant crimson flyleaves. Solicited on a shelf beside competitors, whose covers might be caked in gauche typography and illustration, Little Cat will sell itself through understatement, will seduce with its modesty.

In other words, this book’s violent pornography is very smartly dressed.

Whatever her novellas’ outward couture, Berger herself has no qualms flatly identifying her fiction with porn. Or, more specifically, identifying her fiction through porn. In the afterword of Little Cat, she writes, “I know why I wrote it. It was to sustain this perfect, merciless feeling I had while spitting art’s extremity into the suckhole of porn.” And make no mistake: Little Cat is indeed masterfully rife with extremities, spit, sucking, and holes. In this era of 50 Shades of Bestselling S&M, however, Little Cat does not simply submit itself to a mere handful of flesh-thumping scenes then, having achieved stimulation, roll over and retire.

In a book review for most novels, here you would read a trim, glossy plot summary. In the case of Little Cat, each of its novellas’ plots may best be described as a woman’s extended dream sequence, filtered through the logic of online erotica. There are recurring characters, sure, though it’s not their actions that enthrall—it’s their mental circumstances. Most of the actual acts are sexual anyhow, contained to a few ravaged bedrooms. There are dozens of paragraphs devoted to descriptions of anatomy and mechanics—these scenes are explicit in detail, they foster desire, just as ye ol’ Internet’s porn aims to do, and they all fit squarely within the genre’s established mold. But juxtaposed against these scenes are also long, wrenching sequences whose intent is to make you ache. Psychologically, sexually ache.

The central conflict in these stories is not between the women and the threat of sex. In fact, these women are usually fully complicit. Their desire is firmly stated. The conflict, instead, arises as these women try to reckon with what exactly this desire means. Nearing the final ten pages of “Lie With Me,” the first of the collection’s two novellas, the protagonist, a self-described “slut,” tells an ex about her most recent sexual outing: “‘I think that guy might be wounded for life!’ she laughed. ‘I mean, how can you go back to regular sex after you’ve been held down and fucked by a hot bitch like me?'” The question, in case you or the petrified ex misunderstood, is rhetorical. But it also reads as a lead-in to Berger’s central question for her fiction: In an era suffused with vapid porn, flush with it, can stimulating sex still be shown to transform—or wound—its characters? Again and again Berger’s narrators descend into poetic-philosophical hells, wrestling with what it means to be hypnotized by sex. Or, even more alarmingly, to be self-hypnotized by sex.

Inevitably, the sort of reader drawn to Little Cat, drawn to a sleek exterior caging the heady sex within, will question how this book functions as a feminist document. (Note please the bead of sweat that now tarries on my, the male reviewer’s, brow.) If analyzed according to the contents of its most specific details, Little Cat engages with steamy, methodical, industrialized porn. As such, it paradoxically worships women by placing them in a subservient, hungry role—a contradiction that can be read as either empowering or enslaving, depending on a whole mess of additional philosophical choose-your-own-adventures. Meanwhile, in its language, characters, and dialogue, Little Cat is generally unremarkable, reinforcing most of the stereotypes a reader might expect. However, in structure and logic, the novel thrives.

For instance, each section of “Lie With Me” opens with an epigraph from Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Then, in the novella’s middle, the narrative perspective shifts from that of the “slut” to that of seven of her male conquests. Subversively, though each of these stories starts with the promise of a man’s sexual wonderment, it always ends with the man’s psycho-devastation. As is the case with the guy “wounded for life,” the woman always finds a way to undermine the sexual fantasies of her men. These masterstrokes are subtle, and they take place within the machinery of the sex scenes themselves. By the novella’s end, we come to understand that by having each man recount his tale, Berger is actually mythologizing the woman’s sexual power. The Ovid epigraphs are not mere ornament: they’re a template. Just as ancient Tiresias earned wisdom by straddling both sides of sexuality, the “slut” has earned her wisdom by acting as both predator and prey.

“The Way of the Whore,” the second novella collected, is more traditional in structure, though it takes on an intriguing, if nebulous, consideration of religion. The narrator, Mira, a teenage stripper and hooker from a suburban, Jewish family, descends into an almost prophetic crisis in which her sex games are punctuated by soft language and musings on Biblical carnality. Where this all lands in terms of feminism is a complex matter. Fortunately, Berger herself resolves the issue by effectively brushing it away. It is again the afterword that offers the most incisive observation. Berger looks away from feminism itself and refocuses her attention on the craft of fiction, the craft of voice. She writes, “It was this push-pull of pressures that made me transcribe and complicate the getting-fucked female voice—a voice that I found in porn, a voice that was utterly wasted by porn.”

The notion that porn’s females have fostered an original literary voice is a potent one. Despite all the effort one could spend parsing why a woman ought to write one way and not the other, Berger has done what any good fiction writer should—she’s observed the actual world and has plucked from it an authentic, concrete voice. And, these days, what is observed more intently than porn? What voice is louder, more desperate to be heard— through thin apartment walls, your Macbook speakers—than porn’s? Berger observed, listened, and plucked. She plucked it hard.

Tamara Faith Berger’s Little Cat is out now from Coach House Books.