THE LAST WORD – WAR ENVY

Exhibiting today’s deep cleavage in a haunting and trembling V, an authoritative phalanx of flesh, anthro professor Lindy Powell stands at the head of her lecture hall, watches her students fill the room. Spring light, funneled and dusty through the hall’s academically grand window, makes a natural highlight of her torso’s furled brow.

No student does not notice.

It takes ten minutes for them all to file in, side-glancing like ranks of saluting troops, and as the last pupil settles to its seat, Powell greets her audience, announces an upcoming exam to a roaring response of total silence. The students copy the test date from the board. Despite their various origins and interests, the snot commonly caked in their eyes and their perennial hangovers are some kind of show of solidarity. Whatever that’s worth.

Powell removes her glasses, folds them, slides them into the deep collar of her blouse by one of their arms. She steps abreast her podium, leans against it (it slides under her weight; she narrowly centers herself; the lethal V quivers), and then, with students mostly rapt (fatigued, morale-less), takes a moment to make public her newest hypothesis: that Mike Reemy, a senior seated in the first row, is the Bee’s Knees.

In row twelve, junior Cash Everest, Jr., knows better.

Prof Powell fists Mike’s most recent dissertation, curled into a flimsy scroll, toward the booming lecture hall. Exhibit A. Suddenly there’s no doubting this moment’s severe gravitas.

“Mike Reemy, class, has done it again,” Powell beams. “Five pages of unadulterated brilliance. Intellect uninhibited. Stuff of real substance. Pure, gushing, seminal substance.”

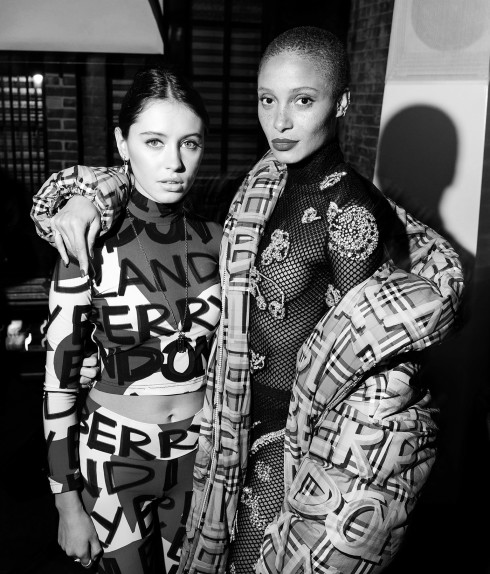

The freshmen salivate. The upperclassmen snooze. Sophomore blondie Sasha Omar giggles at Mike’s side, affectionately whips a finger across his wrist. Mike is a fully scholarshipped football All-American. As Powell makes her glittering pronouncements, he glances over each of his shoulders to spy his classmates’ envy. He attempts nonchalance, fails.

Cash Everest, Jr., gags.

“The work of a scholar,” Prof Powell lisps to the room. “Some really magnificent stuff here, Mike. Really great. Maybe you could take fifteen minutes next class, make a presentation? Give us a taste? Really, kids, this is the work of a scholar, a muscular, enduring—so much endurance— scholar and a…”

She star-gazes Mike’s pocked mug in search of a worthy title. Their eyes lock. Breasts heave. Sasha panics openly.

“A cunt, ma’am!” Cash provides from the back, sings across the rows. A fresh silence falls. Mike’s hammy neck cracks as he cranes backward, and Sasha’s gaping mouth lets airborne a string of saliva as she spins. “Oh excuse me,” Cash continues. “A bloody cunt, ma’am. I refer, of course, to not the person but the thing. I.e. it is remarkable the volume of succulent waste that hemorrhages from the scholar’s mouth. Like a bloody c-word. Not the person, ma’am, but the thing. We’re not British after all.”

A second dramatic, shocking pause until a ginger stoner in row six wearing a Mogwai shirt breaks the hush with a muffled, hilarious grunt.

“Excuse me?” Prof Powell shudders at Cash, hideously agog.

“You know. Brits. The Anglos, ma’am. Of the infamous, heavenly Blitz. Los angeles. The people, not the place.”

Powell’s in a sort of paralysis, but for her warbly flesh. She’s grasping for some articulation. Eventually she manages: “Do you know what you’re saying—boy?!” She recognizes Cash by neither name nor face, despite it being April, approaching the end of spring semester. It is Cash’s first time speaking in class. Two days earlier, he found his app for next fall’s financial aid inexplicably denied, paired with a curt letter forbidding an appeal. So yesterday, finally with a fair motive, he strolled to the off-campus Army recruitment center, enlisted. No friends yet know. He’ll bus out next week.

“Crystally, ma’am. As clear as an unmuddied lake, as an azure sky, etc., etc. And saying it with some fair eloquence, I might suggest. You’d be a fool to fail me.” Cash stands. “Alas. Godspeed in all your unseemly endeavors, Lindy and Cunt.” He makes for the door before Powell can unfurl her meaningless, enraged babble.

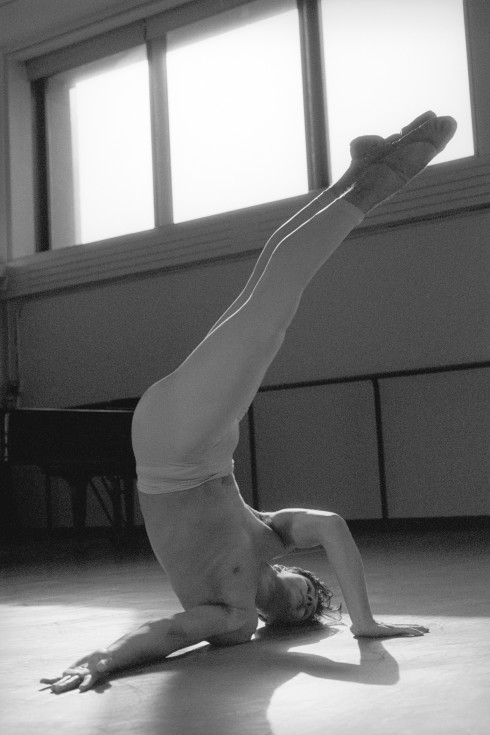

Meanwhile, Elinor Lark, who’s been seated at Cash’s side, flutters to her feet and scrambles upon her slender legs, which slide into her hips with the curve of a katana, but cannot overtake him. He absconds with a slam of the door. Elinor reopens it, turns to the room and gives a coy smile to the querulous gallery of aspiring academics, her braces gleaming, slips through like an eel, and sounds a second crash.

Cash is Elinor’s main squeeze, against her better judgment. But she can’t help it. She feels a loathing attraction to his horrorshows, his enigmatic and unpredictable rage. No doubt he’s brilliant, but angry and brilliant. Some chicks dig assholes. Elinor digs a genius asshole, who, she suspects, can actually articulate his rage if ever put to the test. Unique and wondrous, or, at the very least, infatuating. To appeal to Cash’s taste for the extreme, Elinor hasn’t trimmed her fingernails since they first met, three years prior. Now, the pikes arc eight inches from her glassy hands. (With the exception of those oddities and Elinor’s adult orthodontic work, she is a classic beauty. However, classicisms aren’t her peers’ specialty, and she’s earned the campus sobriquet “claws ‘n’ jaws.”)

But woe: as far as Elinor knows, Cash is an amorous drought. She’s never seen proof of him showing affection to anyone (though she’s heard rootless rumors; his name does make its way through certain clandestine, nearly occult, circles), let alone herself. However, Cash has ceded Elinor a rare license for proximity, which she can only assume is a reward for her loyalty, a minute reciprocation of her affection, and a genuine appreciation for her bodily aesthetic—she’s never heard “claws ‘n’ jaws” from Cash’s lips. He allows her to keep on his heels, and though he often mocks her with crude sexual witticisms, the most substantial manifestation of their relationship occurred one night last year: Elinor fell asleep on Cash’s dorm bed while he, back turned, curled over his desk with pen and paper. When she woke still in the night, she found that he had crawled in beside her. With back propped against the wall, he held her head and dark hair in his lap. Souvlaki spouted from the stereo. He combed his fingers against her scalp until she slept again, woke in the morning to witness his interminable reattachment to his desk.

—–

A half-hour after Cash’s outburst, Elinor sits on the floor of R.R. Rolo’s apartment, a mile off campus, on the distant side of the north woods. Cash is on the couch beside Rolo, who is an obese and hooked Persian, a medical student. In the corner, on Rolo’s stripped futon, lies Quincy, a photo MFA, swatting at a fly. Currently, Quincy is tripping and can only speak in cryptic rock and roll libretto.

“Who crushes a butterfly on a wheel?” Quincy quotes, contemplates. An epiphany gleams across his puss: “I’m standing three miles from space!”

Elinor reaches forward and takes Cash’s foot in her hand, observes the corkscrew curling of a hair, strums it with a claw. He watches and smiles, sincerely. She is thoughtful. She puckers her mouth to the side, in a tick of insecurity. Finally, looking down, she says to Cash, “Why’d you say that stuff to Powell?”

He bucks his foot away with a sneer, turns to Rolo on the couch, leans toward him.

“MEDIC!” Cash screams, a vein making intrusion across his temple, to Rolo’s ear. Rolo’s posture snaps from slouch to full rigor. “Stat,” Cash then sighs in an instant of monstrous melancholy. Rolo reacts with sloth, but finally passes the gas mask on his far side. “Good man,” says Cash. “That’s how we’re going to win this war.” He affixes the mask to his face. With a vermilion lighter, he fries the green dust plugged into twin bowls linked to each of the mask’s faceted nozzles. His chest balloons as he reclines and sucks. Elinor, with knees up and touching, toes pointed inward, watches Cash through her reflection in the mask’s panes. Soon, the smoke saturates then swallows him whole, his eyes fade behind the ghoulish gray, beheading him into anonymity, and all Elinor can see is the convex curve of her own pale face.

Rolo’s hand reaches into the abyss between the couch’s cushions, then withdraws with a vagrant butter knife, its tip crusted tawny. Who knows how long it’s been missed. “Fire in the hole,” Rolo says, then lobs it at recumbent Quincy, where its handle ricochets off of the photog’s crotch, snuggly gripped in his fraying APC’s. Quincy howls. Rolo sinks back to his cushioned indentation, smug.

“This is why,” Quincy gasps, “events unnerve me.”

When Cash finally lifts the mask’s bottom to unveil his mouth, Quincy has settled down to a tormented wheezing and Rolo is drifting towards a nap. Elinor pretends to key her phone, one eye tilted towards the couch.

“Mm gas,” Cash says. “Now, World War, the First. That was a real war. Don’t you wish you could have been there? Just to put all this shit in perspective, or something. I mean, I like the taste of mustard.”

“A superb condiment,” Rolo confirms. He shares a kingly sigh.

“The deadliest,” Cash says with a glancing slap to the dozer’s gut. Cash and Rolo nod in tandem at the profundity of this truth.

“A lot of people are allergic to peanut butter,though,” offers Elinor.

Cash is stunned. He stares in abject disbelief, nearly gets to his feet. Instead he leans forward on the couch. “Not a goddamn condiment!” he screams. He grabs a pipe from the table and takes a quick, furious hit.

“Then what?” says Rolo, quick to fan the flames.

“A spread, maybe?” Cash throws his arms in emphasis. “A filler, perhaps? You can’t call something a condiment if it has full sandwich potential. Peanut butter sandwich? There you go, standard fare. Amen. Mustard sandwich? Fuck you!”

“Who put you in charge?” Elinor asks.

“Do you believe in God?” Cash says.

“No.”

“Then you’ll have to settle for me.”

Elinor stands and walks to the door. It takes her several seconds to maneuver her nails so that she can grip the knob.

“Ellie, hold on. Wait,” Cash calls. “I need one of your WFBJ’s.”

“What?” she says.

“World Famous blah blah blah.”

“What?”

“Oh, deary. One of your mythical blowjobs. You look like you need a JB anyway. Jizz binge.”

“Fuck you, Cash.”

“I bet the braces, claws ‘n’ jaws, add something. You know. Danger. Terror. Takes a beautiful BJ to the level of the sublime. Like getting a massage from the flat of a Bowie knife.”

“The return,” Quincy screams, “of the Thin White Duke!”

Elinor snaps a nail with her second slammed door of the hour.

—–

The evening of the next day finds love-dumb Lady Lark distraught, as Cash has not yet sought her out to make repairs or amends. (Not that she really expected them.) She arrives at his dorm-room door, come poised to receive apologies with grace, or, if necessary, obtain them with force, or, most preferably, she’s ashamed to admit, charm them from his depths with Eros’ litany and tongues, Ellie’s thin white tongue.

The door is a crud-caked, cracking affair, a bulk of tawdry, enigmatic material (not wood, not concrete, not steel) shielding the even more enigmatic contents and contours within. It’s hinged with springs and formidably weighted, and shuts automatically—a dorm precaution to prevent scatter-brained students from exposing their burrows to the whims of the cruel, covetous world. Cash lets his often slam. Doors seem always to slam around him.

Tonight, though, Cash is inviting some intrusion: it’s been propped ajar with a sandwiched rubber boot, and within, behold, he’s absent.

Elinor, not unfamiliar with the place, musters the necessary courage and goes inside to await his return. For a moment, she appraises the option of ambush versus diplomacy. She elects the latter. She sits on Cash’s bed, her usual perch, in what she hopes is a judicious pose. The floor’s carmine linoleum is lightly scuffed by her swaying feet. The walls are bare-bone, but for a dark speckle behind the desk where Cash once gushed a spurt of blood after a fumbled whittling of a tiny oak chess pawn (later painted cream and sent home, tenderly gifted to his little sister for her birthday). Dust and paper—scraps, whole sheets, and bookfulls alike—vie for territorial domination of the room. Only a notable rectangular clearing on the desk is allotted a pristine space, and there lies a trilogy of leather notebooks: black, black, and black. Above, privileged on its own shelf, sits the stereo. The rest of the desk is an arrested avalanche of other scattered sheaves—flayed tomes, unaddressed postcards, pistol schematics, anatomical drawings, anatomical massacres, and simple, elegant sketches in Cash’s utilitarian hand of pretty and incising girls, whose faces Elinor cannot recognize or place, sure they’re not classmates, and who bring her not jealous doubt, but wonder.

Every surface and deposit of Cash’s room is ornamented with gleaming strands in layered crosses, or in lonely lines, or in curled balls: Cash’s dead and ossified hair, patiently but always, always balding from his head (which he often shrouds in public with a hood), tumbling like sand, he has said in delightfully self-aware melodrama, through an hourglass. He’ll be, roundly marked as less Spartan or Seraphim than modern man, bald by twenty-five.

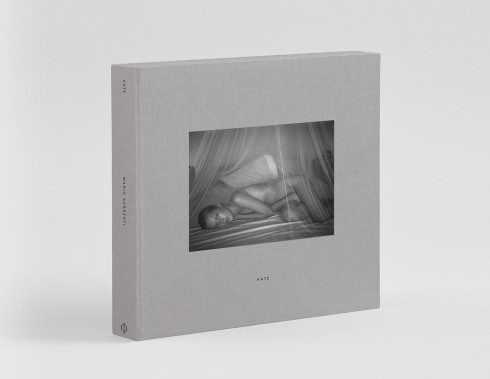

Elinor’s not been here alone before. She leafs through a bed-marooned monograph of George Rodger’s Battle o’ Britain photos. Twice she thinks she hears a creaking and that the door is opening and that she senses some oncoming rage, some rosy light and rising heat—but nothing. She puts down the book and sits silent for a full minute. Then, moxie suddenly shot, stands and flees the room. She leans against the wall in the corridor outside and slides to a squat, ready to wait here. But presently she hears the squirrelly chatter of Demi Dwyer, spiritual kin to Sasha Omar. With horror Elinor squints down the hall at Double D, who is gamboling nigh. The law of flight—something, Mr. Bernoulli, about lift and pressure and least resistance, elucidated somewhere in Cash’s room in a facsimile manual of aerial mechanics, circa 1943—propels Ellie back across the hall, back to Cash’s private trenches.

—–

After an hour, a purring nap on Cash’s cot, she’s still waiting. She sits up and sways on her hips toward the window above the bed’s foot. Dark out now. From here on the third floor she sees on the fringe of a street lamp’s cone two boys sitting on the grassy slope. Nobody else between here and the woods. They trade a joint between them. One is too far in the dark to be made out, but the other is closer to the light, and he seems drenched in something, dripping from his hair, from his saturated denim-coated legs, which he has pulled to his chest with his arm. As they smoke they toss against the dorm building a tennis ball, which ricochets back to them off the albino bricks between the windows of the second and third floor.

Restless now, Elinor fixes herself at Cash’s desk. She thumbs open Black Notebook I, the topmost, and inside finds more sketches. A dozen or so, all of an apparent series. They depict scenes from the life of a father and young daughter: Walking hand-in-hand through a field of tall grass. Riding a crosstown bus, ice cream cones beginning their deliquescence in the glare of the sun-side window. Asleep on an engorging couch, the adorably drooling daughter sprawled across her father’s chest. And on the last page of the series Elinor discovers nothing but three dark pencil lines, evenly spaced: perfectly sable streaks vertical on the page, milled into the paper so harshly that she can see where the sheet began to thin and rupture. There is no explanation offered; the rest of the notebook is obstinately blank. A triangle of exterior light opens across the desk, grows, and then collapses back to a rod.

“My tender Lark,” says the light. “Wherefore, pray tell, where-fucking-fore, are you at my desk?” The boot booted away. The door slams shut behind him. “Been scouting long? Satisfactory findings?” He stands leaning.

She closes the book and rotates in the desk chair toward him. “I was waiting for you. I—”

“Waiting for me? In my room? You are a clever one, Ellie. Don’t ever let them tell you contrary. You’ll get far, far, far. Perhaps.”

“I was waiting for you. I want to talk.”

“I want to scream.” Cash grins, leans harder.

“I want to talk.”

“Of course you do.”

“Can we talk?”

He turns down his hood. He batters the light switch on the wall with the monstrous fat of his palm and the buzzing ceiling lights go mute and defunct. Elinor straightens in Cash’s chair as he comes up behind her in the dark. He reaches about her neck. There is groping and then a click as he seeks, finds, and turns on the emerald-shaded banker’s lamp. Elinor’s face set in the ivy radiation. He sighs, standing above her, she still facing the desk. Her hand is on the notebook. She sits rigid. She does not look back. All inert but the indulgence of their human machinery: breathing.

“These are really good,” she finally submits to the void. She turns the notebook open to its first page. Kitchen scene. Orange juice. Beard. Small hands. Cash looks down upon it. He lifts Elinor’s arm, moves it from the page. He closes the book and replaces it to its stack.

“Please get away from my desk.”

Elinor does not move. She sits Catholic with hands in lap. She looks at the notebook. “But what’s that last picture about?” she says, nods toward the question. Cash pauses. He retrieves the book from its pile. He opens it to the scene of Couched Nap. “This gem?” he asks.

Elinor says no; she turns the page. The three graphite slashes unfold.

“Oh yes. This last page.”

Elinor does not speak.

Tracing his finger against the textured lines, Cash clears his throat affectionately.

“This is when the bombs fall.”

“What bombs?”

Standing behind her, Cash rests his chin atop her head. He exercises his jaw against her peak, hair whorl, moving open and closed several times. Then he says, “The bombs. Always, always bombs.”

Elinor looks back through an incidental curtain of her hair, strangled there between her head and shoulder blade. “You’re twisted,” she says.

“Maybe. I doubt it.”

Elinor starts to pivot the chair. Cash halts her with hand on shoulder. He turns her back toward the desk. He then reaches toward her spine—the six knobs of her torso running up, as if there were a golden strand threaded through, through halos, or staples. Suggesting tensile strength greater than Kevlar, texture smoother than skin of, well, a girl like Ellie. Precious. He massages her back for several silent minutes; sectioned flesh; calloused fingers; capable hands.

—–

“Where were you?” Elinor asks. Cash’s hands work on.

“Someplace else,” he says. “Someplace illicit and lurid and lewd.”

Elinor simply shakes her head.

Cash sighs. “I was getting food, okay? Magnificent pizza rations. Doctoring my hunger. But… but would you know about that?” He stops the massage. He reaches down to her waist and grips and raises her shirt to expose her flank up to the bottom scoop of a breast, puts thumb and forefinger on either side of the sharp protrusion of a rib, pinches. She pulls away with a yelp, repairs her shirt, clasps his hand away. She slams the chair against his legs and he stumbles back and she stands from the desk and slips past him to the bed. Cash stands blinking and then looking at the fingers that have just repelled his own.

“They’re gone!” Her fingers are cleanly trimmed and filed.

“They got in the way,” she flatly says.

“‘They got in the way,’ she says,” he says. “Sure they did. You just didn’t like being a freak.”

“I wasn’t a freak.”

“Of course you are, and let us not pretend otherwise.” Cash takes on his trademarked scholarly pose, resonant tone, honed sneer, with hand in hair and nose shaped in aquiline ascent. “You cultivate freakish looks, freakish tastes. You,” a jab, “haunt, freakishly, the rooms of freakish boys. You have self-imposed the condemnation of freakhood.” Head shaking. “It’s foolish to fight it, Elinor.”

“I’m tired of your bullshit, Cash. I’m tired of caring about you.”

“Then go away. I don’t believe you were invited.” Elinor stands from the bed, hands dug deep pocketwise, fidgeting, writhing. She turns toward the door, stares it down. In audience, Cash offers his tacit applause. Elinor envisions her next fifteen seconds: the storming out, the breakaway to the stairwell where rage/frustration will fuel her for at least one storey before mutating to a daze of self-pity and confusion, paralyzing her en route between floors one and two, where she will squat above a Trident-crusted step for the majority of an hour, then eventually heading home or back to Cash—neither conclusion satisfactory. In the midst of these conjectures, standing before him, who has at this point conceded to sit in his own desk chair to observe her deliberations, she makes a stationary 360. Surveying the room in desperation for some third option other than To Stay or To Go. The room she finds: draped in any flavor of carnage but barren all the same. She stays. She tosses one of the pillows against the wall and it falls doubled back to the bed and she falls in turn upon it, curled on the sheets away from Cash, face holed into the corner of the room where the bed meets the walls meets a girl’s gray eyes.

Visions of a valley. An ambush. A truncated retreat. A trench. A tunnel. A cavalry on high stripped free of their mounts in contortions of force. A field of grass like a canvas for some carnal art. A descent to its middle. A serious misunderstanding. Shrapnel punching through the line. A punchline, a bad one.

Cash regards her private crisis with what appears to be a certain solemn respect, him familiar with the whole tortuous world of staying and leaving. I.e. the Battle of Absent Mother, 1999. The Siege of Anonymous Father, initiated 1989, ongoing.

“Better trigger finger, at least,” he says in condolence. Still faced against the wall, she reaches a hand behind her head, shapes it into a sideturned L, cocks the thumb, the polished platinum hammer of the rare and powerful E-model Colt mini hand cannon, officer issue, aims it blindly, right at Cash’s flawless forehead, and with a jerk of wrist says in flaccid breath, “Bang.”

Direct hit. Cash’s mind eye, situated in triangulation to the standard two (in terms of imagination Cash is a stubborn Cyclops, albeit with 40/20 vision from that single orb) sees itself blasted against the wall, splattered, to both his and Elinor’s vicious pleasure. Impressive. So, enflamed, he spoons her. Remarkable speed, precision, menace. And they do get close fast—her elbow, his throat. His esophagus flattened, a real pop now, gurgling, a blissful spinning of eyes. He tumbles from the bed to the floor, laughing and coupled in spasms of coughing pain until he hacks a salmon-colored phlegm. He rolls it in his palm.

Elinor peeks her head, terrified, over the edge of the bed down above him, like a child checking her killing jar. She’s got concern on her face, her mouth slack for worry. When Cash sees her braces, that persistent sterling in her head, he’s sent into a second salvo of hysterics.

“Jaws!” he cheers and beats floor with fist. “Ready to board my moonraker?”

“Huh?”

He waves the question away.

They lie. On their respective slabs. Into silence and late-night. Elinor listens to the hollow pings of the boys’ tennis ball outside, arrhythmic, but still striking sightless and loyal, sometimes rapidly, sometimes with mounting lulls, until finally there’s one beat, and then another, and then, with no sort of warning at all, with no puttering out or tightness in the chest or numb left arm, nothing comes next.

—–

“I think I’ve said enough to Powell.”

“She won’t let you back into class, I bet.”

“Ergo, I won’t be going back to class, I bet.” Cash strips off his shirt, tosses it supine from the floor up onto bed where it drapes her face. His black skin is not lit by the lamp, which fails to pitch its light that far from its stance on the desk.

“Then you’re failing the class,” she speaks into his stains of sweat.

“Wrong, okay? You manage to pry even without the claws. I’m not failing anything. Everything’s failing me.”

“What’s your fucking problem?” Elinor says.

“Right now, my fucking problem is your noncompliance, dear.” The irony is not lost on love-struck Elinor, nor the repulsion. “My life problem? War envy.”

“What do you mean?”

Cash holds her close against his chest. He sees his mama’s face. Junior, she calls, and he climbs up to her knees and palms. June bug, she says. In his resurrected mind’s eye, he holds his face against her chest, just as he holds Elinor before the eye of God, and he drifts into a kaleidoscope of that image of comfort.

“Do you feel safe?”

“From what?” Elinor asks.

“Exactly.” He rolls back into the floor of dust. And this is how he always sees it. Rolling for his life from bedpost to bedrock, guard tower to bunker. The fall indisputably preferable to whatever’s been fallen away from. A slow dive, steady descent is Cash’s choice course: the only one that makes sense—because what beats gravity? Even those who pretend to, with breakaway velocity screaming through ozone, suicide-strapped to monstrous bellies of rocket fuel, with heat-resistant tiles, with voluntary vantage through a fishbowl, will never really escape. Let them break Earth’s orbit, only to meet some new celestial shape and its own new tether and the eventual realization that though gravity gets weaker with distance, it never disappears—only settles in to some infinite and boundless web. So even at the edge of all possible flight, escape, or exodus, Earth’s force is on our backs—not enough for us to feel, not enough to fix any measurable enslavement, but there all the same, as present as a fact and as permanent as a brand, as ubiquitous as our understanding of omnipresence allows. So Cash likes letting gravity work for him. But the thought has crossed his mind: What if there’s a bottom to hit? He rehearses to his mirror, existential. A: I’ll pummel through. But till then—what?

—–

“It’s so fucking stupid to fail like that.”

“I’m not failing.”

“Alright.”

“I’m not.”

“I said okay.”

“I’m quitting.”

“What?”

“I’m out of here.”

“You’re dropping out? Are you serious?”

Cash shakes his head then holds his hands before him in a manual shrug, as if cradling a kid. “I enlisted.”

Elinor laughs like a mushroom cloud. She turns her face away. Her last stand kicked out at the knees, now so obviously overpowered, devastated, leveled. Cash’s instant supremacy and, subsequently, her surrender. His secret movements all found out, suddenly snapped into a formation of terror, blotting out the sky into something alien. All she has left is terrible, honesty. “I swear to God,” Elinor says, “I hope you die.”

“What, doll?”

She lets her sobs get violent and she pulls his wifebeater tight across her face and gasps against the accumulation of their mingling fluids there. “You’re enlisting, you bastard? I hope you die. You deserve it, you asshole. I hope a bullet pierces both your lungs or something crazy like that or you get captured and waterboarded with an ocean and a grenade blows off both your legs or your gun misfires and takes off your own face or you just do something stupid and painful and terrible to yourself like that and fuck Cash I just wish you’ll die.”

“I might, you know.”

“GOOD.”

He sits up and watches her pull the cloth against her anguished face. He reaches halfway toward her, hovers. “You’re not too good at dirty talk.”

“Stop it. I’m serious. I won’t take this anymore. You really are the dick I was so afraid you were.”

“I’m sorry.” He grips her dangling wrist.

“Don’t touch me. Don’t ever, ever touch me.”

She cries until shivering, a pall of grease across her cheek, a pillow garroted against her chest. Her infamous teeth chatter. Her gaze is a wound, perhaps the one aspect of war Cash left overlooked. No feeling, she thinks, is left unbetrayed.

“I’ll be fine,” Cash says.

“Dead’s not,” she screams, “fine.”

When she stands to go, she makes no hesitation until she’s on the far side of the door, propping it with her hip. “Don’t die,” she says toward the door itself.

“Not my goal.”

“Then Jesus, Cash, I don’t know what is.”

He looks up. Smiling and shaking. Briefly, they live together in that shared vibration.

“You have my love,” Elinor says.

He laughs. “Love?”

“You know I love you.”

Cash shows first rage and then some unmatched depth of human pit, pain. “Of course I didn’t know that.”

=====

Cash went off to war. He did not die, but he did see death, was close to it. He served the time of his tour and then came home.

He saw Elinor once on a beach. He was walking by and she lay sunbathing upon a yellow towel, her body cut by the elegant azure of her simple bikini. She recognized him passing and yelled to his back, leaned up on an elbow with her stomach creasing in its taut yew folds, a hand drawn across her brow to block the sun. Her husband was in the water with the dog. She called Cash over, waved full-armed, glowed. He sat beside her in the sand. They caught up.

Suddenly, Elinor put her hand on his (the sand swallowed both) and looked to his eyes. “Did you find what you were looking for?” she asked. She smiled, hopeful. And there they appeared: her teeth were pearls, bare and strong.

Cash wept into his hands.

Time had turned her skull to a shrine. He had no defense for that.