WHO TOWN

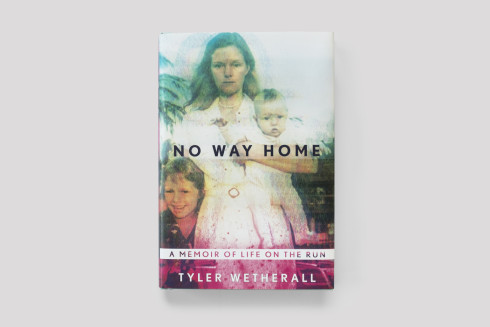

For her début novel Who Town, New York writer Susan Kirschbaum drew on her experience covering art, fashion, and certain social scenes in the city as a journalist for over a decade, lending the social parody an eerie air of realism. In Kirschbaum’s vivid portrayal, the problems and places feel real—it’s easy to envision scenes set not only in New York neighborhoods, but also in particular places, like the venue a young band plays on the Bowery, though she doesn’t name it. And issues of self and celebrity culture remain constant. While Who Town tells a tried tale—a mix of archetypal twenty-somethings struggling to find, define, and lose themselves in city culture—Kirschbaum reinvents the unraveling in a way that feels relevant. Who Town is the story of youth and identity, art and fashion, drugs and rehab, the scene and the sex, but for the next New York generation.

Released in May, Who Town has drawn comparisons as the present-day, downtown-New York answer to Bret Easton Ellis’s 1985 novel—also his first—Less Than Zero. It presents an East Coast take that follows Sarah, a disillusioned celebrity reporter who crosses the line into the life of her latest subject. What once excited Sarah about the city, the downtown crowd, and her budding writing career feels distant, though she’s more in it than ever. “After almost three years with the Tribune, Sarah’s subjects reminded her of the fireflies she used to collect in a jar in her yard as a kid,” Kirschbaum writes. “All she did was net them. With a blunt knife, she’d punch holes in the lid, so the trapped insects could breathe while they danced in the container, illuminating her bedroom. And unless she set them free, they would fall to the bottom of the jar and die. Then, she’d flush them down the toilet and gather new ones.”

Sarah’s editor runs her through a succession of It Girls, focusing on each until she fades out and it’s on to the next one. This time, it’s Roxy, a socialite and pseudo-artist known more for her Tribeca loft parties than her sculpture. Sarah borrows a Dior dress from Roxy to attend a film screening party—thrown for Roxy’s lover Lola, an erotic actress—which her editor asks her to cover. But Sarah arrives off the record and does a line of Roxy’s cocaine before slipping out with a cheap but charming fashion photographer. Their lives all come together and fall apart, the latter applying particularly to Lola, who develops a heroin habit with a bar back in a bathroom in Williamsburg.

Kirschbaum reveals the difficulties that arise when the lines between subject and reporter are blurred, and touches on the guilt that comes from covering the tawdrier side of the celebrity spectacle. “Lola, I’m sorry,” Sarah says at their intervention upstate. “We use you to test boundaries that scare us. We like that you shock us. The media and publicity machines prod you with prizes and attention because your pain makes us feel safer in our own skins. But if you go any further, you’ll die…And then we’re all guilty.” Sarah’s story runs in the paper shortly after, as though nothing happened. On to the next one.