ANA ISABEL KEILSON

It was Ezra Pound who once said something to the effect that poetry loses its way when it gets too far from music, and music loses its way when it gets too far from dance.1 Music is not something to which one dances, Pound would have us believe; one dances and the gesture necessitates music. First comes the body, the physicality of life, and from that everything else follows in good order: music, poetry.

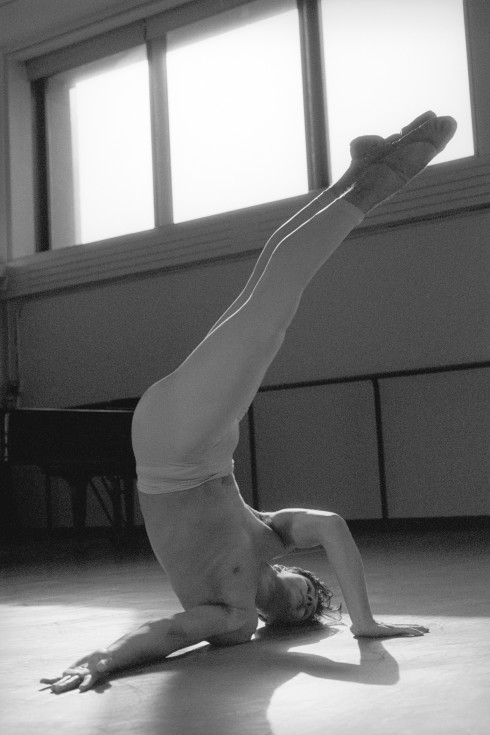

Ana Isabel Keilson’s latest piece, Fanny and Alexander and Fanny and Alexander (for six)—which had its New York début two Fridays ago at the 92nd Street Y’s most recent session of the venerable Fridays at Noon series—would seem to prove Pound right. And although it might be disconcerting at first to discover that music is not the map here, Keilson’s choreography invokes a small world of its own, one that seems to find its guiding logic in the problem posed by movement itself. In this new work, the dancers (Rebecca Arends, Elizabeth Coker, Kesa Huey, Pareena Lim, and Jin-Ju Song-Begin, as well as Keilson)—a competent group of artists, expressive, representing a broad range of dance training and physicality—quite literally summon music to the piece, ushering a violinist (the talented Hanna Morrill) onto the stage to play the violin’s part of the second movement Schumann’s Quintet in E flat major. Technically Fanny and Alexander and Fanny and Alexander has its own score, written by Louis Schwadron; recordings of birds overlaid with a recording of the same Schumann quintet function as prelude and coda to the performance. But despite these incursions, much of Fanny and Alexander and Fanny and Alexander unfolds to the sound only of dancers moving across the stage.

This embrace of silence might sound distinctly (perhaps disconcertingly) like the hallmark of postmodern dance, but it would be too dismissive to ascribe that label to Fanny and Alexander and Fanny and Alexander and let it go at that. Keilson has called her work “unfashionably neoclassical” in general, or, more playfully, the “modern-dance lovechild of the ballet barre and the folkdance.” Her pieces fall somewhere between the radical experimentalism of the downtown set and the somewhat more conservative culture that defines dance in midtown. But it is that very grounding in classical lyricism—set off by gestures at times heavily weighted towards the ground, a great deal of floor work, movement that is at times frenetically enthusiastic—that makes her work so engaging. Fanny and Alexander and Fanny and Alexander evokes that strange incongruity of spontaneity and, at the same time, flow, that odd pairing which describes almost all dance that is delightful to watch.

Despite its title, Fanny and Alexander and Fanny and Alexander is not a dance adaptation of Ingmar Bergman’s 1982 film of (almost) the same name. Nor is it a response to that deservedly classic film, nor would it be right to describe it as a tribute, although the Schumann quintet makes up a prominent part of that work’s score as well. This charming and deeply intimate work is what might best be called a Variation on a Theme by Ingmar Bergman: it is a portrait of a relationship between a brother and sister, one that Bergman himself left remarkably underdeveloped in his story. Lifting this relationship from the film and elaborating on it, Keilson builds her piece largely around a series of overlapping pas de deux, three sets of partners, each expressing different facets of intimacy, play, and the secret games children invent with one another. Despite a relatively small company, the space seems filled, at times even perhaps a little too busily, each dancer showing a different side of Fanny and Alexander, similar to a Cubist portrait that fractures unity in order to better depict reality. Partners change, but we almost always have three Fannys and three Alexanders, dancing together but never entirely in unison. Each partner contributes something different, but together they create a coherent singularity: what one might call, in other words, a relationship.

Traditionally, the pas de deux is a heavily gendered convention, loaded with an implied sexuality that is all well and good so long as you don’t mind too much hetero-normativity when you sit down to enjoy the show. Fanny and Alexander and Fanny and Alexander escapes those traditional strictures and instead presents a different idea of partner dancing; the company, which is entirely female, does not approach the idea of relationship as one of either/or, but instead as one of synthesis. Is there a major partner? A minor? It’s hard to say. Keilson has said of her work that she approaches it asking, “What is the world that I want to build?” In this piece, she has in fact built a world within a world, where children speak their own language, sometimes even whispering to one another on stage. The viewer is allowed to look into the special world that exists between Fanny and Alexander, but we are not privileged to its rules. It is a mirror of the experience of adult men and women who share the world with youth, who can no longer know all its workings but who are cheered to be a part of it.

1The actual quotation, a little too organic for my taste, is from Pound’s fascinating and oftentimes exasperating ABC of Reading: “Music rots when it gets too far from the dance. Poetry atrophies when it gets too far from music.”

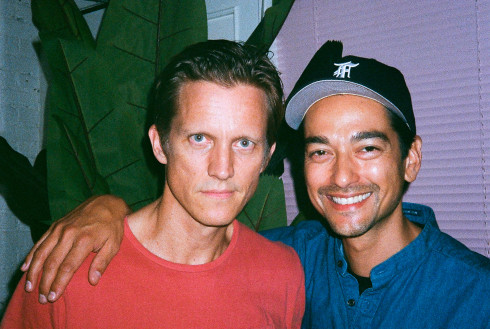

For more information, please visit AnaIsabelKeilson.com. Photography by Julie Lemberger.

Jason Resnikoff lives in New York. His work has appeared in The Paris Review, The Faster Times, Tropics of Meta, and on stage at the Cherry Lane Theater.