BODIES IN SPACE

What can we do with our bodies? Two new documentaries by Wim Wenders and Frederick Wiseman explore the question. Naturally, the films are physical ventures: bodies writhe in the dirt and glitter through Lurex pantyhose, they slide up and down poles and under tables and chairs. Like some of the earliest films made, Pina and Crazy Horse communicate through silent choreography of the human form. Without language, both films effortlessly break down the fourth wall between the audience and the screen.

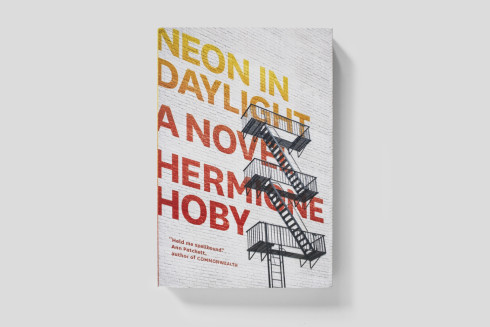

Pina is a documentary about the dance of legendary choreographer Pina Bausch, by her dear friend Wim Wenders. Wenders spent fifteen years trying to come up with a visual solution to the inherent problem of dance on film. Then in 2007, he saw U2 3D, the first-ever 3D concert film. “From the opening frames, I new I had found the language I’d been looking for,” Wenders concedes. Inspired and excited, he rushed to tell Bausch and immediately began planning the film. She died weeks later and only five days after being diagnosed with cancer. Undeterred by the tragedy, her dancers encouraged Wenders to continue the project. The film is a dutiful tribute to her work, as well as a manifesto for the future of 3D filmmaking.

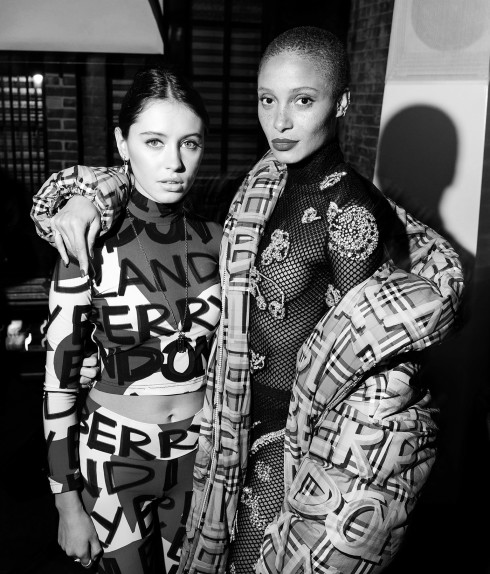

Crazy Horse takes us deep inside the infamous Parisian cabaret as it prepares to celebrate its sixtieth anniversary. We get an exclusive look at the creation of a new show, appropriately titled Désir. For sixty years the Crazy Horse, or simply “The Crazy,” as it is affectionately called by those intimately involved, has produced a rigorous study on the psychology of desire. Continuing his career of fly-on-the-wall documentaries, Wiseman adds another to the list of films about the “various uses the human body is put to.” Most recently, he has made Boxing Gym, and before that La Danse, concerning the Paris Opéra Ballet. Crazy Horse can be seen as an odd bridge between the two. It is a study of the intersection of art (dance) and commerce (the marketing of sex appeal). Like Pina, Crazy Horse contains a cast of incredibly talented performers who do unthinkable things with their bodies. And for the viewer, both films deliver physical experiences beyond cinematic.

To achieve this, Wenders and Wiseman ignored what most documentary filmmakers do first: interview. The Wiseman approach insists his camera be part of the atmosphere. Tellingly, when we see a television camera crew interviewing the creative and artistic directors of the Crazy, Wiseman’s camera is entirely ignored. And the only voices you hear in Pina are juxtaposed over portraits of the dancers. We hear them share anecdotes, but their lips don’t move. The effect is disarming, a non-talking head.

The lack of language allows the bodies on screen to tell their stories. At the Crazy, we meet dancers who have trained in ballet for most of their lives. Artistic decisions there may have more to do with the silhouette of one’s posterior than the pointe of one’s toe, but the skills are the same. The dancers practice rigorously with obsessive attention to detail. Eroticism has been boiled down to an exact science, and the Crazy troupe is satisfied with nothing short of perfection. Their rehearsals offer a naturalism that is missed during the performances, where any authentic emotion is extracted. Anxieties are stifled. Here, body language is the native tongue.

Wenders adamantly made “a film without language.” Structured around four fully-realized pieces performed on a stage, the film also takes us into the city of Wuppertal, Germany where the troupe is based. These passages give individual dancers time to tell their own stories. In mesmerizing solo performances, Wenders explores the psychology of dance and the genius of Bausch. Wenders mirrored her directorial approach by posing personal and philosophical questions. One dancer described how Bausch “saw something I was afraid of.” By taking dance off of the stage and into the streets of Wuppertal, Wenders puts his characters into an alien environment, something only film could achieve.

Pina and Crazy Horse are films about performance that fixate on how the body is used as means of communication. Both films are also about filmmaking. Editing is of paramount importance to non-narrative filmmaking, particularly to two filmmakers whose directorial approach is to shoot first and assemble later. As per film editor Walter Murch, “editing is not so much a putting together as it is a discovery of a path.” The terrain through which the directors trudge is dense and aimless, hundreds of hours of footage with no natural order. The subject of dance allows Wenders and Wiseman to pursue bodies in motion and construct intimate portraits of life lived physically.

The greatest storytellers make us identify with the protagonist, seeing the world through their eyes and feeling what they feel. The best filmmakers make us live in their world. There is a scene in Pina that begins with a 16mm film projector directly in front of the camera. A man walks up to the projector and turns it on, causing grainy black-and-white images to appear before it. There is nothing revolutionary about this scene except for the simple fact that we see it in three dimensions. This modernist moment reminds us just how different the technology is.

Pina and Crazy Horse accomplish more than any show-and-tell; they seduce our bodies before our minds, bringing us not into a fantasy world but back to reality. As the curtains part, the screen becomes a stage. We peer around the heads of fellow audience members (Crazy Horse) and down from the balcony at the first few rows of seats (Pina). The movie theater immediately becomes the cabaret and the auditorium, respectively. Not since the Lumière Brothers have filmmakers so successfully broken down the fourth wall. As soon as Wenders and Wiseman pull us onto their stage, we are under their spell. What proceeds is an ode to the magical capabilities of motion pictures and the beauty of bodies in space.

Pina opens today. Crazy Horse opens on January 18, 2012.