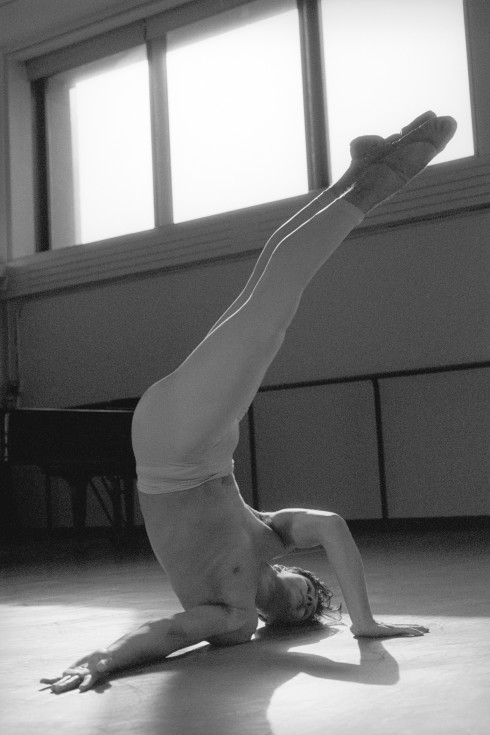

JONAH BOKAER

One afternoon last December, the young choreographer Jonah Bokaer gave a tour of the Center for Performance Research, a warren of offices and studios in a LEED-certified residential building on the far end of Williamsburg. Moving from the risers in the whitebox performance space to the empty storefront, he paused to tidy up a pile of finger paints left over by an afterschool children’s arts class. “The work that I make often deals with large-scale visual and installation components,” he says of the provocative, leading-edge dances he has been crafting since 2002. “So having a space that could house that work for development was very important.”

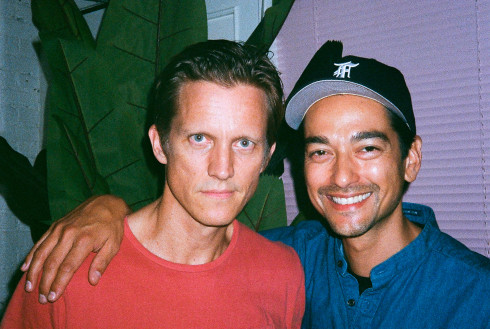

The CPR—which Bokaer opened in 2008 with fellow choreographer John Jasperse—serves an important place in the neighborhood and the larger surrounding arts community as well, providing an environment for others to practice their craft in a city that is perpetually lacking in affordable places to work. Bokaer’s appreciation for his position as part of a greater creative network goes against the stereotype of the lonely artist concerned only with his own creativity. “This is a space which is not purely about John or about me,” he says. “It’s about there being a space for performance and performance research, for just trying things out.”

Bokaer, whose dances do not easily fall into any category more specific than the generic catch-all “modern,” characterizes himself as a “choreographer and media artist.” He works at the nexus of an array of artists across a variety of fields—dance, music, fashion, sculpture, video, architecture, and design, for starters—whose interdisciplinary collaborations represent a veritable hive of new-media interplay. “I look for collaborators who not only create remarkable visual works or artistic statements,” he says, “but who can create a whole world, or a whole planet.”

A frequent collaborator is Daniel Arsham, a visual artist and partner with Alex Mustonen in the architecture firm Snarkitecture. For Bokaer’s “Why Patterns,” from 2010, Arsham and Mustonen planned for a torrent of five thousand ping-pong balls to rain over the dancers. In 2009’s “Replica,” a pair of performers slide through two holes punched into a wall placed at the center of the stage. “Not only does he create a visual premise for an installation, he designs a space, he designs parameters, he designs roles and interventions, and feeds the collaboration and the piece quite substantially,” Bokaer says of working with Arsham. “In our process, the design elements form the fundamental premise for the choreography.”

Arsham also designed many sets for Merce Cunningham, the legendarily meticulous choreographer in whose company Bokaer danced from 2000—when he was eighteen—until 2007. “I worked with Merce for seven or eight years, and we had a deep, artistic, creative bond,” Bokaer says. “I think he created ten works on me when I was with the company, and I got to interpret three of his roles, so it was a close working relationship. He was very patient, very professional, very methodical.” Bokaer says this first-hand experience with Cunningham’s creative process helped shaped his work as an artist. “I was drawn to the visual components and the operatic way of working with music, dance, and light,” he explains. “It was very chance-based, aleatory, and kind of radically independent. But I also have evolved a career far beyond that early modern school of thought.”

While Bokaer’s choreographic style differs in many obvious ways from Cunningham’s, the elder artist’s legacy is clear in Bokaer’s fascination with the melding of dance, music, and design. Cunningham was famous for his insistence that choreographer, composer, and artist work in isolation from each other, a practice that produced a long run of indelible contributions from his close circle of friends and partners, which included John Cage, Robert Rauschenberg, and Jasper Johns. Bokaer has flipped that idea on its head: for him, the partnerships and the relationships between the collaborators are integral to the work at hand. “I also have been very inspired by a lot of other artists such as Robert Wilson, artists who really do participatory collaborations,” he explains. “And that I think has had a stronger impact on how I’m working now.”

Bokaer, a media studies major, also pushes boundaries in another direction, the technological, incorporating video and other newer types of media as integral parts of his performances in a way that questions the existing structures of dance. “I was seeing a lot of performance work, a lot of choreography that used projections just as a backdrop, and my sense is that there are more integrated ways of media production,” he explains. “If you think about early video art or installation art, there’s such an intense grammar behind how to use projection, so I’m looking at that when I make performance work and not just using it as something decorative, but to push the form of performance.”

The next innovative step in Bokaer’s study of the uses of technology is a dance app produced by the 2wice Arts Foundation planned for release this spring. “What we’ll be doing is creating a dance which is intentionally designed for an iPad or iPhone, treating that space like a proscenium stage,” he says. “We’re creating a box, which will be in proportion to the window of an iPad or iPhone, and, in the same way that when an iPad or iPhone flips, the space rearranges, when the space reorients, I’ll be reorienting my body in that box so that once the user flips that screen, there will be different angles for the dancer to be performing in.” Aside from serving as an introduction beyond his current audience, the work becomes, in effect, a dialogue between the dancer and his audience. For Bokaer, it’s an opportunity to invite the viewer in, turning him into yet another partner in the creative process.

For more information, please visit JonahBokaer.net.