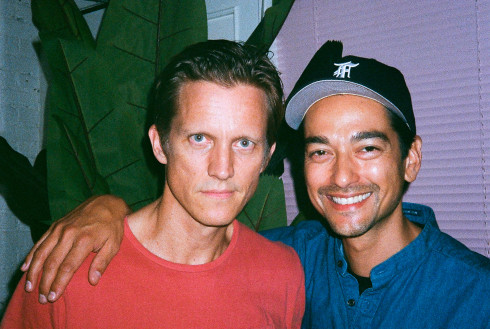

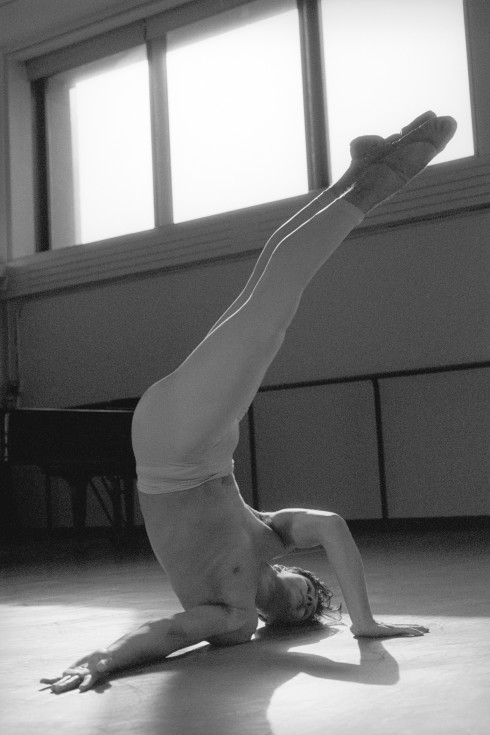

JUSTIN PECK

Last November, the New York Choreographic Institute celebrated its tenth anniversary with a selection of works from some of its most prized and most promising alumni. Alexei Ratmansky, Christopher Wheeldon, and Larry Keigwin— each a brand name in his own right—presented new works set to the same piece of music, and a collection of principal dancers from New York City Ballet performed that evening. And yet, the night’s highlight was “Tales of a Chinese Zodiac,” danced by teenage students from the School of American Ballet and crafted by Justin Peck, a young City Ballet dancer who started choreographing only in 2009.

“Tales of a Chinese Zodiac,” set to three short sections from Sufjan Stevens’ propulsive thirteen-piece Run Rabbit Run cycle, was intricate and complex, the dancers covering the stage in an ever-changing series of formations that altered course often but felt entirely of a piece. Peck, who knew little about the Chinese zodiac beforehand, immersed himself in studying the music’s context before considering the steps. “I really love [Stevens’] thematic way of making music, and it gives me a lot to work with in terms of how much background research I want to do,” he says. “I checked out a few books and started researching what is behind each zodiac animal so I could take that information and use it as inspiration and translate that into dance.”

Most people watching that night knew Peck better as a corps member at City Ballet, where he joined the company in 2006. Peck had his first onstage experience at the age of thirteen as a supernumerary in an American Ballet Theatre performance of Giselle. “I kicked and screamed and fought it to the end, but I ended up having to do it, and actually I was very inspired by the athleticism of the male principals there,” he says. “I wasn’t aware that men could be such powerful dancers.” From there it was a few short years of catch-up classes before Peck was asked to join the School of American Ballet. “It was kind of my excuse to run away to New York City,” he laughs.

Over the past few years, Peck has worked as a dancer with several choreographers to create new works, a process he says has allowed him to learn from the masters. “Every time I work with a choreographer, I try and make a list in my head of what I like about working with the choreographer, and then a list of what I don’t like,” he says. “It’s a big learning experience and hopefully it’s helping me evolve as a choreographer myself.” Besides, of course, Balanchine and City Ballet ballet master Peter Martins, Peck cites another artist who has made a lasting mark on his home company as an examplar. “Most of Ratmansky’s stuff has been hugely influential on me, I think because I got to work with him and he’s someone who has true vision,” he says. “He comes into the studio with this notebook of formations and patterns and everything. I’ve attempted to model my own process in terms of being prepared after him.”

With only a handful of works under his belt, Peck expects to dedicate more time to choreographing in the future, although any opportunities that arise must compete with both his dancing and his classes at Columbia, where he is a part-time student in the General Studies program. “I had this craving for some sort of intellectual stimulation that’s a completely different way of thinking from how we’re trained to think [at City Ballet] in terms of remembering choreography and working in the studio and the physicality of it all,” he says of his decision to study anthropology and art history while his peers can barely find enough time at the barre. “It’s hard to fit it all in,” he admits, but that intellectual discipline feels absolutely vital for someone who explains of his work, “I find inspiration everywhere.”