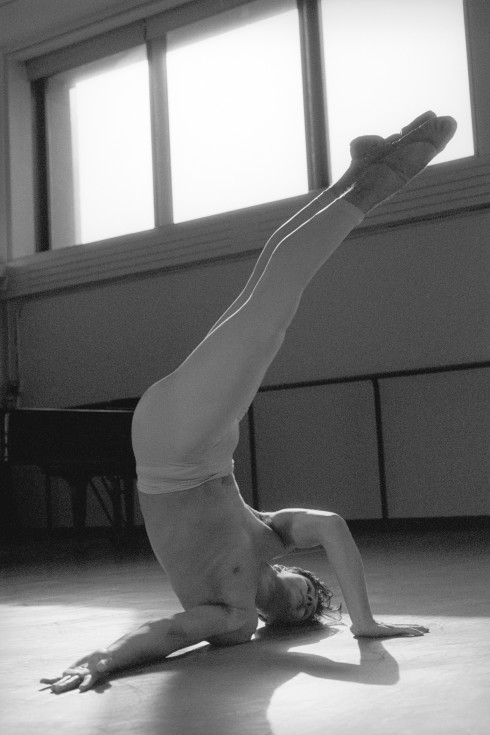

'A (MICRO) HISTORY OF WORLD ECONOMICS, DANCED'

How do you dance the economy? How can we know the dancer from the dance? These are two questions that pervade French playwright and director Pascal Rambert’s A (micro) history of world economics, danced—co-presented over the weekend by La MaMa, PS 122, and the French Institute Alliance Française (FIAF) as part of FIAF’s 2013 Crossing the Line Festival—in a theater production that explores our collective economic history throughout centuries of time from the islands of Polynesia to fair France. In one hour.

Inspired by the recent European economic crisis, the piece was originally composed with the participants of the writing workshop at the Théâtre de Gennevilliers. Participants drawn from non-professional groups were invited to write about the joys and sorrows of dealing with mundane economic issues of their lives, from job-hunting to repaying debt. Then they were asked to take part in body workshops where they translated the written word into the moving body. The result is an emotionally potent choreography of simple gestures and daily actions. When Rambert went on tour to New York, he took with him only three actors from the original company (Clémentine Baert, Cécile Musitelli, and Virginie Vaillant) and a philosopher of economics, Professor Éric Méchoulan of the University of Montreal, who helped him think about the ideas of economic history and who is also one of the main actors. In New York, Rambert again set up workshops with over forty non-professionals to create a local version of the show.

The production has many moving parts and is quick on its feet. With the help of the three professional actors, we jump from one scene dramatizing one bubble in history to another. These are brief sketches illustrating locales as diverse as Mr. Lloyd’s Coffee House (where the insurer Lloyd’s of London was founded) in seventeenth-century London, a Polynesian gift-exchange ritual, and an evening at the poet Stéphane Mallarmé’s salon. In between, Méchoulan delivers lectures on economics explaining what we’ve just seen. What makes Rambert’s piece truly unique and imaginative, however, are the moving bodies of the non-professionals, who rarely leave the stage and who continue the choreography of their daily actions throughout the performance. When needed, their bodies are also employed to illustrate the historical background, such as the workers of a mirror factory or the moving parts of Blaise Pascal’s 1642 mechanical calculator.

Theater usually tackles economics through the drama of ideas—in other words, through lots of talking. In the discussion plays of Ibsen and Shaw, bourgeois characters pace around stale drawing rooms and talk ad nauseam about the prevailing economic issues of their day, from inflation to labor conditions. Brecht was even more didactic. He brought the actors and audience together in the appropriately named Lehrstücke (learning-plays) to rack their brains in search for solutions to social plights.

Rambert turns Brecht on his head. If you were hoping that the acclaimed production would offer a crash course in the history of world economics or explain the subprime mortgage crisis of 2008, you may have left disappointed. Pedagogy is not the main point of Rambert’s fascinating and multifaceted work. The production is at its strongest when it shows, not tells. In fact, Rambert might be slyly suggesting that talking in the theater is not enough, that mere talking doesn’t use the medium’s full creative and utopian potential. Sure, there is a real and an intelligent philosopher of economics on stage, but paying attention to his words, however wise, requires focus and patience. This is not to say that the lectures are not insightful, just that Méchoulan’s remarks about labor, the means of production, and the management of fear can be lost amid the bustle as the bodies of non-professionals pantomime their daily mundane activities. Their labor rarely stops, and the moving, kaleidoscopic tableau of colorful figures absorbed in their tasks, each in his or her own little world, is beautiful.

During the lectures and playacting, our attention is inadvertently drawn to these so-called amateurs. They are the heart and muscle of the performance. Their bodies of flesh and bone refuse to go away to make room for the actor or the philosopher to claim the spotlight. There they are, real-life New Yorkers going about their everyday tasks: brushing their teeth, shaving, showering, going to work, eating, typing on laptops, unscrewing bottles, etc. Except they mimic doing these things onstage on a weekend, and therein lies the beauty and revolt of their actions.

These locals from different ages and backgrounds found the time out of their busy lives to be part of a theater production. They came to rehearsals not to get paid but to engage in what, from the standpoint of capitalist culture, is unproductive labor. They found time to create communal art with other strangers and to share this experience with an audience. If only for the brief duration of a performance, Pascal Rambert’s A (micro) history of world economics, danced does not just relate history. It creates, before our very eyes, an artistic utopia.

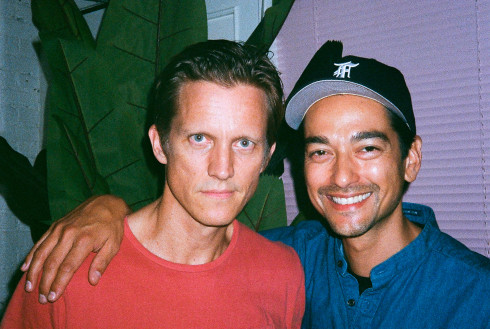

Photography by Ilan Bachrach.

Alisa Sniderman is a writer based in New York. Her writing has appeared in Salon, the Los Angeles Review of Books, Rumpus, and Eclectica Magazine.